Violin

- Home

- Violin

Overview over the violin, its history and violinists

Andrea Amati, the worlds oldest Violin

The violin is certainly the central figure of the violin family. An instrument of much fascination, romance and mystery that is paired with a fascinating history of craftsmen and players. The roots of the instrument are unfortunately lost to any reliable scholarship, but it is generally accepted that the Violin began to emerge circa 1495 to 1505. The initial framework for its players was generally in a “consort” or paired within a small ensemble. At the time the aristocracy still viewed it with some disdain, as the lute and viol were still in vogue as instruments of choice. However, this gradually grew to change as the Violin became increasingly popular as an accompaniment to dances. The first Violin craftsman is again another subject open to intense debate, but some scholars credit Andrea Amati of Cremona in Italy as the first. His instruments however were not the design that we know today, as they had only three strings and were closer in function and musicality to the rebec, a common ancestor of many stringed instruments. Other scholars credit another Italian Gasparo di Bertolotti da Salò, this is primarily due to Amati being described as a “lute maker”. However, there is an exemplary piece of his craftsmanship still existing, and is considered to be the world’s oldest (but by no means the finest) Violin.

By the 1600’s the Violin’s star had began to rise, with composers like Claudio Monteverdi employing the Violin in his operas. By the beginning of the Baroque period the Violin had well and truly shed its common preconceptions with hugely influential figures like Antonio Vivaldi (his Violin concerto series “The Four Seasons” is one of the best known pieces of all time) and Johann Sebastian Bach, utilizing it in many of their compositions.

The first musician to truly earn the title of Violin virtuoso was undoubtedly Niccolo Paganini. An incredibly skilled musician and somewhat notorious figure, he both created a number of pieces that influenced many generations of ensuing players and composers (his “Twenty Four Caprices for Solo Violin” showcased many of his original technical and compositional elements) and was a consummate showman. His notoriety and flair for the dramatic did much to establish some of the intrigue that is now associated with the violin. He also was shameless in his talent for self promotion. Creating rumours that he perfected his talent while imprisoned for murder, and more darkly that he used a murdered mistresses intestines to string his Violin. It was this and his real life propensity for gambling and vice that lead him to be refused a Catholic burial upon his death. His personal foibles aside the mans consumate skill and performing talent ensured his legacy, and his cult of personality inspired future musicians like Louis Moreau Gottschalk to play up their personal lives in order to promote their music.

A depiction of Paganini

A romanticized image of Stradivari, by Edgar Bundy

It would be a cardinal sin to mention Paganini without giving due credit to the maker of some of his instruments, Antonio Stradivari. A contemporary of Amati, but he was to comprehensively out-shadow Amati’s legacy within his own lifetime and on the pages of history. His Violin craftsmanship was marked by experimentation, both in design and musical innovation. His work survives even today; to play a Stradivarius is considered to be the crowning achievement of many a violinist. One of his pieces, the “Lady Tennant Stradivarius,” was sold on auction in 2005 for a (then) record breaking two million dollars. Few craftsmen of any discipline could have had such a defining effect on the development of their craft.

In the modern era there are many incredibly influential musicians who play and compose for the violin, far too many to list here. It is a question of musical style, teaching lineage and personal preference that informs who could be said to be the greatest Violinist of the twentieth century. However two names come to mind, Jacha Heifetz and Eugene Ysaye.

Heifetz is for many the definition of a prodigy. His first serious musical foray was at the tender age of ten for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. There is an incredible anecdote regarding the consummate skill of the young man in this period. After one of his performances in Berlin he was invited to dinner at the home of a noted critic. He was asked to play by his host, and Fritz Kreisler (at the time the most popular Violinist in the world) volunteered to play the alongside him performing the Mendelssohn Concerto. Upon its conclusion a stunned Kreisler remarked “Well, gentlemen shall we all now break our violins across our knees?”.

As he aged, his skill and dedication to performance only grew. By comparison to Paganini he despised showmanship, preferring to let the music speak for itself. He never rested upon his laurels, once remarking “If I don’t practice one day, I know it. If I don’t practice two days, the critics know it. If I don’t practice three days, the public knows it”. Given the accolades he received during his lifetime and from such a young age, it is remarkable the humility and lack of hubris surrounding the man. His dedication to charity and activism is well noted. After his death in 1987, the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic, Glenn Dicterow (he had been a student of the man late in life), said “To me, he was the most human of all violin players. We’re all children compared to him. He never had any competition but himself”. It would be hard to think of a more fitting epitaph.

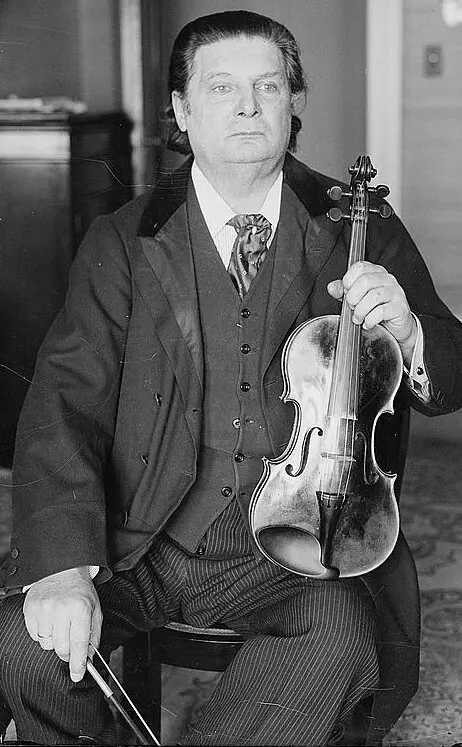

Jascha Heifetz

Eugène Ysaÿe

Not to be out-shadowed by Hefietz, Eugène Ysaÿe was in his own right a truly remarkable musician. Born in 1858, he began his study of the medium at the age of five, under the instruction of his father. He was prodigious in his talent, entering into the Conservatory at Liege at the age of seven. A devotee of the French school of Violin scholarship, he exemplified its bowing technique and sense of musicality. After his graduation, he played in what was to become the Berlin Philharmonic, until at age twenty seven began his career as a soloist playing for the Concerts Colonne. Following this, he received a posting at the Brussels Conservatory, which was to begin his lifelong commitment to teaching. As his health declined he rededicated himself to the other forms of music, both conducting and composition. He was to live by his credo “do nothing which wouldn’t have for its goal emotion, poetry, heart”.

In conclusion, while an article like this can only but touch on the vast history, scholarship and performance of the violin, it is hoped that this brief look at the Violin and its history will serve to inspire and engage students and appreciators to delve further into its study.